The Context

In this century, it is typical for dogs within a breed to be bred to a prescribed breed standard. For example, if a dog was taller than specified in a standard, breeders would eliminate the dog from the breeding program, or breed the dog to a smaller mate in order to bring down the size of the next generation. In this way, the individuals within a breed maintained a particular look that made it easy to identify as a member of one breed and no other.

How is a breed standard determined? Sometimes the breed standard is based on observations on what is the ideal form for a particular man-made job or function. To put it in very simple examples, a thin body as found in the sighthounds was more ideal for running down hares. A substantial body as found in mastiffs was more effective in stopping poachers and robbers. Thus evolved the saying "Form follows Function."

As people started to own dogs as pets that were no longer used to performed a function, the idea evolved that if a particular form was maintained, the dog or its descendants could theoretically still perform its function if they were ever asked to. Therefore, elaborate and sometimes unfounded explanations were written in order to maintain certain features. The immediate fallacy of this idea of "Function follows Form" is that it omits the mental component that is needed to perform a function. Of what use would be a thin body if there is no desire to hunt hares? Of what use would be a substantial body if the dog cowers around intruders? The long-term fallacy of believing in "Function follows Form" is that it leads to extremism among the unwary and can lead to the physical determent of the individual dog.

Extremism occurs when competitive breeders go one step beyond "Function follows Form" with "If a little of this is good, then more of it must be better" and they never test out their theories by working their dogs. Their motivation changes from "preserving the breed" to "improving the breed." This can lead to overangulation of legs, underangulation of legs, overabundance of coats, too frail of a frame, too heavy of a frame, and so forth.

How does this situation relate to the Jindo breed and the Jindo breed standard?

In order to preserve at least the form of the Jindo, it's important to recognize the foundations. The Jindo is often described as nature-made and not man-made. For example, many of their owners never dictated that all Jindos must hunt fleet deer, or must hunt dangerous boars. Instead, Jindos hunted animals the Jindos themselves picked and in a hunting style they themselves decided on. Some Jindos learned by trial and error which prey animal they were best at catching and the manner which is the best for their build.

Therefore, being a hunter is not the sole driver of why Jindos appears as they do although it is the most easy to track. There are many other pressures which are not necessarily issues in man-made breeds:

-Ability to cope with incliment weather while wandering

-Ability to deal with the flora and fauna of their environment

-Ability to discriminate among mates (females rejecting inadequate or related males)

-Ability to defend and maintain territories

-Ability to birth naturally

-Ability to efficiently wander long distances over variable terrain and then find their way back, etc.

Therefore lies the dilemna of those writing standards for the breed.

-How to be inclusive of Jindos but not so inclusive that it allows extremisms or deficiencies?

-How to best reflect the Jindo's origins of being molded by nature?

-Should the standard describe a master hunter of a particular style or should it amount to describing Jindos as "jack of all trades but master of none"?

For these reasons, there are many different standards for the Jindo within Korea, and some specify one style while others specify several. All should attempt to strive to "preserve the breed" as nature made it and not "improve upon it" as man might whimsically decide.

Components

1.

Throatline

2.

Withers

3.

Shoulder

4.

Prosternum

5.

Forechest

6.

Brisket, ribcage

7.

Loin

8.

Croup

9.

Tail

10.

Flank |

11.

Belly

12.

Groin

13.

Underline

14.

Chestline

15.

Shoulder joint

16.

Upper arm

17.

Elbow

18.

Forearm

19.

Wrist

20.

Pastern |

21.

Forefoot with toes

22.

Paw

23.

Nails

24.

Upper Thigh

25.

Stifle joint

26.

Lower thigh

27.

Hock

28.

Rear pastern

29.

Hindfoot with toes

30.

Dewclaws |

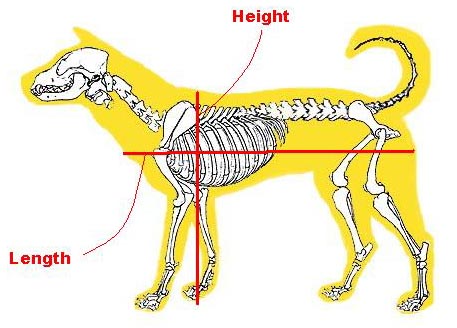

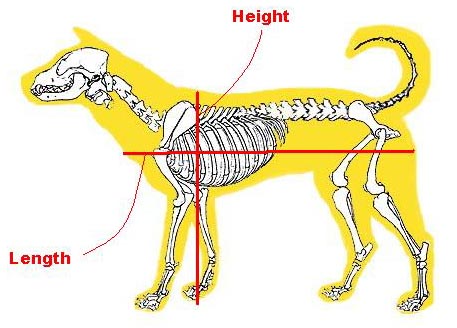

Overall Body

Most Korean Jindo owners can pick out two body types for the Jindo and colloqually use the terms gyupgae and heutgae. Gyup literally means folded and heut means scattered.

The heutgae is usually easy to pinpoint,

with their racier, leaner build. They tend to have less depth of

chest and a slightly long loin (space between the ribs and the hips), resulting

in an appearance that is longer than tall. They tend to have

longer features... longer or slighter head, longer ears, longer muzzle, etc.

The gyupgae is widely acknowledged

as being stockier and more muscular than the heutgae. They

give the impression of power rather than speed.

Gyupgae body type

photo by Mr. Im, In Hak |

Heutgae body type

photo by Mr. Im, In Hak |

The Korean National Dog Association uses relatively new terms such as Tonggul

(equivalent to gyupgae), Hudu (equivalent to heutgae), and Gakgol (blend

of the two).

Tonggol body

photo by Mr. Woo, Mu Jong |

Gakgol body

photo by Mr. Woo, Mu Jong |

Hudu body

photo by Mr. Woo, Mu Jong |

Ideal proportions for a Jindo will vary depending on each organization's point of view. Some organizations pick

only one set of proportions while others allow for differences between

the heutgae and gyupgae. The proportions for the gyupgae is

especially diverse. For instance, the KNDA recognizes that for

gyupgaes, proportions are 10:10 and for heutgaes, proportions are 10:11.

Another source, a Jindo Island evaluator, differs and says that gyupgaes

have exactly the same proportions of heutgaes (100:110) with the only difference

being the heavier bones and increased muscle mass on gyupgaes.

Desired heights will vary per organization as well, but it cannot be emphasized enough that

this ambiguility about height does not give free-rein to breed whatever

sized Jindo a person wants. Many breeds have suffered from fads...

going to miniature to giant size. The Jindo, in recent years, has not

been immuned to people who think smaller is cuter or bigger is better.

However, true fanciers of the Jindo breed realize that the Jindo is foremost

a natural breed. The Jindo is the size it is because it needed to

have a body size large enough so that could hunt for prey on its own but

small enough as to not waste energy in maintaining bodily functions.

Breeding away from this natural state makes a Jindo no longer a Jindo.

Narrowing down weights is slightly less

complicated. A gyupgae and a heutgae might have the same height,

but their weights are expected to be different due to the gyupgae's bigger

bones and corresponding increased muscle mass. Looking at the

condition of the dog, whether the animal is pure, mixed, underfed, overweight,

or in peak condition overrides any absolute weight criteria.

Different organizations have set different

ranges of what they would consider desirable height/weights in Jindos.

The following is just a sample.

Table from the KJCCA website

|

MALE HEIGHT (cm) |

FEMALE HEIGHT (cm) |

RATIOS |

HanKook JinDotGae ChukSanHyupDongJoHap

"Korean Jindo Dog Livestock

Raising Cooperation" (roughly trans.) |

45~58 |

43~52 |

. |

HanKook JinDotGae HyupHei

"Korea Jindo Dog Association" |

49~55 |

45~50 |

100~110 |

DaeHan JungThong JinDotGae

HyupHei

"The Traditional Jindo Dog

Association" (roughly trans.) |

49~53 |

47~49 |

100~110 |

HanKook AeWanDongMoor BoHo

HyupHei

"Korean Pet Protection Association"

(roughly trans.) |

50~55 |

45~50 |

100~110 |

HanKook JinDotGae JoongAngHei

"Korea Jindo Dog Centrel

Committee Association" |

52~55 |

48~53 |

100:110~115 |

Table compiled from other

sources

|

HEIGHT |

WEIGHT |

RATIOS |

| Korean National Dog Association |

Male 49-53 cm (19-21 in)

Female 48-51cm (19-20 in) |

. |

GyupGae 10:10

HeutGae 10:11 |

United Kennel Club (U.S.A.)

(based on the KNDA standard, before revision) |

Male (desired): 19.5-21

in.

Female (desired): 18.5-20

in. |

35-45 lbs

30-40 lbs |

GyupGae 10:10

HeutGae 10:11 |

Federation Cynologique Internationale

FCI |

Males: 20 - 22 in.(50 -

55 cm),

ideal 21 in. (53 - 54 cm)

Females: 18 - 20 in. (45

- 50 cm),

ideal 19 in. (48 - 49 cm) |

18 - 23 kg.

15 - 19 kg |

10:10,5 |

| HanKook JinDoGae HyulThong

BoJon HyupHei |

Males: 48 cm ~ 53 cm

Females: 45 cm ~ 50 cm |

. |

100:110 |

Official Jindo Island Standard

(before revision, from their

old website) |

White Male: 48.98cm +/-

4.16cm

Red Male: 47.62cm +/- 4.07cm

White Female: 45.15cm +/-

3.13cm

Red Female: 45.39cm +/-

3.21cm |

20-30 kg (44-66 lbs)

under 20 kg (44 lbs) |

. |

Topline

When viewed from the side, the Jindo's

topline consists of curves rather than sharp angles. There is a two-fold

reason for this... function and astethics pleasing to Koreans.

The functional reason will be explored under the Movement section.

It's been said that the Jindo gives the

impression of being drawn with a brush, while the Japanese breeds are drawn

with a pen. Curves and gradual transitions makes the Jindo "natural"

to the Korean eye.

For the readers who are more attuned to

comformational terms, the following describes the curves in the Jindo pretty

well.

"The topline inclines very slightly downward

from well-developed withers to a strong back with a slight but definite

arch over the loin, which blends into a slightly sloping croup. The ribs

are moderately sprung out from the spine, then curving down and inward

to form a body that would be nearly oval if viewed in cross-section. The

loin is muscular but narrower than the rib cage and with a moderate tuck-up.

The chest is deep and moderately broad. When viewed from the side, the

lowest point of the chest is immediately behind the elbow. The forechest

should extend in a shallow oval shape in front of the forelegs but the

sternum should not be excessively pointed. "

--from the original United Kennel Club Jindo Standard

Although one Jindo book states that Jindos

have a straight,

level back rather than the aforementioned topline, this opinion seems

to be in the minority. Certainly, it is not desirable for a Jindo

to have a swayback though.

Neck

The neck is thick, relatively short and

muscular without loose areas. It's desired that a Jindo be

dry-skinned... skin is tight against the rest of the body.

When walking or standing, the neck is normally

carried low like a wolf.

Forequarters

The shoulders are moderately laid back,

with moderate angulation and well-developed muscles. The forelegs are shoulder-wide,

straight and muscular, with heavy bone and strong, moderately short, slightly

sloping pasterns. The shoulder blade and the upper arm are roughly equal

in length. The upper arm lies close to the ribs but is still very mobile,

with the elbow moving close to the body.

legs line up with shoulders

(borrowed from Shiba Inu

diagrams)

|

photo by Mr. Woo, Mu Jong

|

Hindquarters

The thighs are very muscular but the muscles

are long and well-defined. The rear legs are moderately well angulated

at stifle and hock joints. The upper thigh is long and the lower

thigh is short. The hocks are tough, elastic, and well let down. Viewed

from the rear, the rear pasterns should be parallel to each other; from

the side, they should be perpendicular to the ground.

Feet

The feet are of medium size, round in shape,

with thick, strong pads. Toes are short, well arched and tightly closed.

Floppy rear dewclaws are usually removed if present at birth.

rear feet

|

front feet |

photos by Ann Kim

|

The shape of the feet is extremely important,

especially in light of how Jindos had to travel for days sometimes when

they had to hunt for food on the island. A poorly constructed foot

would cause the dog to go lame after traveling only a short distance.

photos by Ann Kim |

There are some Jindos that are born with

rear DOUBLE-dewclaws. The double-dewclaw is not at all desirable

and it was the conclusion of one judge that saw them that it negatively

affects the movement of the dog. (Dog compensates by turning legs

outward, which creates inefficient motion and adds stress to the hips.)

undesirable rear dewclaws

Tail

The tail is thick and strong and set on

at the end of the topline. The tail should be at least long enough to reach

to the hock joint. The tail may be loosely rolled over the back or carried

over the back in a sickle position. The tail fur is long, harsh, and straight.

If the dog has a curled tail, the tail

should held straight up and then roll into a curl. Some dogs have

physical discomfort when their tail is manually unrolled due to the tightness

of the curl but the length of the tail should be long enough to almost

touch the hocks of the dog. The curl is held above the body and

fur outside of the curl (usually lighter or white) is obviously longer

than the inside of the curl. Tightly curled tails that are resting entirely

flat against the body and of somewhat even, short fur lengths are frowned

upon. A proper curled tail should evoke the image of a hand

fan held upright rather than a donut laying on the flank or back.

According to a breeder of champion Siberian Huskies, an overly tight tail

negatively affects the movement of the dog when traveling for long distances.

It makes sense that the same applies to Jindos which had to travel long

distances in order to hunt for their food. Some organizations further

divide this catagory into right, center, left, curled, and hooked.

|

Examples of fur on the

outside of curl being white.

|

photo by Johnathan Lee |

photo by Patty Etherington |

The sickle tail is preferred for hunting

Jindos as people like to believe it is a throwback to wolves.

The tail can be pointed straight up like a sabre-sword or forward like

a farmer's sickle.

In some circles, the curvature of the tail is also believed to be influenced by how the puppy is raised. Constant use of the tail for balancing is believed to loosen the tail muscles before setting into its adult form.

|

Examples of saber tails

that point straight up.

|

An example of a tail

that resembles a farmer's sickle.

|

Photo

by Jhun Kim |

photo by Johnathan Lee |

Anus

The anus is an unusual topic to include, however, many Korean descriptions will specifically mention it. Perhaps it is reflective of the strength of the dog's digestive trait and the ability to constantly process bone matter?

It should be large

and muscular on a Jindo, reminiscent of a closed fist. Black skin on a Jindo is desired.